Ben Goldacre is the author of the Guardian column Bad Science (and eponymous blog). Dr Goldacre is a champion of rationality in a world enamoured with sloppy thinking, uncorroborated anecdotes and dodgy statistics. For many years he has been at the forefront of the battle against the pernicious MMR vaccination scare that took a hold of the British media some years ago, a scare that has had negative health implications in the present time. As part of that campaign, Dr Goldacre posted a 20 44-minute clip from broadcaster Jeni "Vulnerable passionate, strong" Barnett (yes, there is a missing coma or hyphen between vulnerable and passionate; and yes, there seems to be a contradiction in terms between being vulnerable and strong). The clip came from a 3-hour live show in talk radio LBC (London's Biggest Conversation), and Ben included it as the perfect example of the anti-vaccination, anti-science agenda that prompted the MMR scare in the first place. However, this clip proved too much for LBC's lawyers, who sent a letter to Dr Goldacre demanding the immediate removal of the clip because it infringed the station's copyright. Dr Goldacre has since complied with the letter. Was LBC justified in their demand? Was Bad Science right to comply?

This is a straightforward fair dealing case. For those readers located in more enlightened copyright territories, the UK has an exhaustive list of non-infringing acts, commonly known as fair dealing. Other countries have a more open-ended approach, such as the fair use doctrine. Fair use allows for a much wider interpretation of what constitutes a non-infringing act, while fair dealing is considerably more restrictive. Nevertheless, s30 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988 allows for the use of copyright works for the purpose of criticism, review and news reporting. The relevant part of the section reads:

"30 (1) Fair dealing with a work for the purpose of criticism or review, of that or another work or of a performance of a work, does not infringe any copyright in the work provided that it is accompanied by a sufficient acknowledgement and provided that the work has been made available to the public."

So far so good. The radio show was certainly made available to the public, and the purpose of the clip was that of criticism and review. Dr Goldacre even invites his readers to mine the clip for platitudes and play some form of Bad Science Bingo, calling out each canard. However, the question here is that the published clip is too long.

To my mind, the question at the heart of this issue is one of balance between copyright, public interest and freedom of expression. Thankfully, there is an authority which deals precisely with this question, that of

Ashdown v. Telegraph Group Ltd. In that case, former Lib Dem leader (and now Lord)

Paddy Ashdown wrote some minutes from a meeting held with Tony Blair. A substantial part of those notes were published by the Sunday Telegraph, so Lord Ashdown sued for breach of confidence and copyright infringement. The Telegraph lost the case and appealed on the grounds of freedom of expression, and they lost that as well. While the final ruling did not favour the Telegraph's freedom of expression defence, Lord Phillips adopted a three-pronged test for cases dealing with the interface between copyright and criticism and reporting. The elements of the test are: 1) whether there is commercial competition between the parties; 2) the public interest and/or human rights implications; and 3) the amount and importance of the copied material. Using this test, I believe that Dr Goldacre may have received a positive ruling if he took this to court. Let's look at each one of the elements described:

1) Commercial competition. This evidently favours the Bad Science blog as the clip in question was not made available in the Guardian, it was published in a non-profit blog clearly for the purpose of criticism. While one could argue that Ben Goldacre makes a living out of the Bad Science brand (via books and his Guardian column), it is obvious that he is not in the same business as LBC.

2) Public interest. This part of the test also favours Dr Goldacre. There are few topics of more importance than that of health, and the health of children is of particular interest to society. The MMR vaccine scare has been a national shame for many years, one that has even led to an increase in the recurrence of measles amongst the relevant infant population. In my view, there is overwhelming public interest to continue to expose those who perpetuate the lie that there is something wrong with the MMR vaccine, and I strongly believe that any court would be forced to take this view in light of the evidence.

3) The amount and importance of the copied work. This is definitely where Bad Science has some problems, as by any measure the clip is quite extensive. It could be argued that a 20-minute extract from a 3-hour show is not too much, but this is definitely where the plaintiff's lawyers would have a better chance of success. Nevertheless, I still think that the previous two elements trump the length argument.

Beyond the strict legalities of the case, one has to feel that Bad Science has done nothing ethically wrong, on the contrary, the reproduction of the clip serves the public interest. Those who espouse the blatantly damaging view that MMR should be trashed, and worse, use their public standing to further such myths, should be held accountable. It is typical of those with indefensible positions to use, misuse and abuse copyright law in order to stifle debate (Scientology anyone?) Copyright law serves a clear purpose to society, but when it is used to censor and remove contrary opinions then the public interest should prevail.

Ben Goldacre has taken down the clip, which is understandable due to the forceful nature of the legal threat and the uncertainty in the law. Thankfully, this is the user-generated era, and nothing remains hidden for long. The clip is now

hosted elsewhere, and there is even a

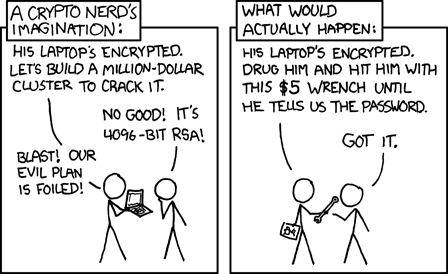

transcript somewhere on the Interwebs. This should serve as yet one more example that the Internet does not take censorship lightly, and any attempt to remove information will have the exact opposite effect, and prompt its viral reproduction.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us